Anasazi and Paiute Indians

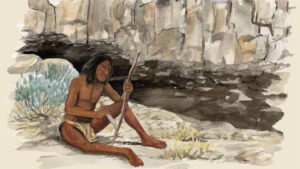

More than a thousand years ago, an ancient people lived here. Today, they are known as the Ancestral Puebloan people of southwestern Utah (formerly Virgin Anasazi). This area offered them shelter, water, a nearby hot spring, and habitat full of wildlife. They lived in and near small caves at the base of south-facing cliffs where recent archeological excavations revealed evidence of their lifestyle in the form of weapons, tools, and crude ropes made of hair and rawhide.

More than a thousand years ago, an ancient people lived here. Today, they are known as the Ancestral Puebloan people of southwestern Utah (formerly Virgin Anasazi). This area offered them shelter, water, a nearby hot spring, and habitat full of wildlife. They lived in and near small caves at the base of south-facing cliffs where recent archeological excavations revealed evidence of their lifestyle in the form of weapons, tools, and crude ropes made of hair and rawhide.

Victor Hall, author of “History of  LaVerkin,” wrote, “During the 1930s, a children’s outing wasn’t complete unless a couple of arrow or spear points were found. A metate, or grinding stone, [could be] exposed when ploughing…”

LaVerkin,” wrote, “During the 1930s, a children’s outing wasn’t complete unless a couple of arrow or spear points were found. A metate, or grinding stone, [could be] exposed when ploughing…”

Later inhabitants, including the Southern Paiute, lived along the banks of the waterways. They practiced limited irrigation agriculture and grew corn, squash, melons, gourds, sunflowers, and more. Their traditional patterns were threatened when European explorers and settlers began to arrive.

First European Explorers

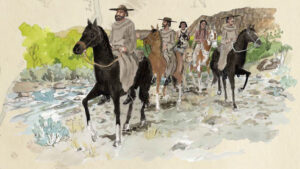

The Dominquez-Escalante Expedition of 1776 produced the oldest surviving written account describing the confluence. this area. The expedition left Santa Fe, NM, on July 29 with the goal of reaching the Spanish mission in Monterey, CA. Along the way they were to map their travels, find possible locations for Spanish communities, and share their Christian beliefs with Native Americans. After traveling through Colorado and northern Utah, cold weather and dwindling supplies forced the group to turn back in early October and return to Santa Fe. They started traveling southeast, and on October 15, 1776, while following Ash Creek, they recorded:

The Dominquez-Escalante Expedition of 1776 produced the oldest surviving written account describing the confluence. this area. The expedition left Santa Fe, NM, on July 29 with the goal of reaching the Spanish mission in Monterey, CA. Along the way they were to map their travels, find possible locations for Spanish communities, and share their Christian beliefs with Native Americans. After traveling through Colorado and northern Utah, cold weather and dwindling supplies forced the group to turn back in early October and return to Santa Fe. They started traveling southeast, and on October 15, 1776, while following Ash Creek, they recorded:

Here we found a well made mat with a large supply of ears and husks of green corn which had been placed on it. Near it, in the small plain and on the bank of the river, there were three small corn patches with their very well made irrigation ditches… We continued south downstream (still on Ash Creek), and after going half a league swung to the southwest, getting away from the river; but a tall embankment without any [possible] descent made us backtrack… until we returned to the river, which here flows southwest. Here two other tiny rivers enter it, one which comes from the north-northeast (LaVerkin Creek), and the other from the east (Virgin River). The latter consists of hot and sulphurous waters, for which we named it Rio Sulfureo. Here there is a beautiful grove of black poplars, some willow trees, and rambling vines of wild grape… We crossed El Rio del Pilar (Ash Creek) and El Sulfureo (Virgin River) near where they join, and going south we climbed a low mesa between outcroppings of black and shiny rock. After climbing it we got onto good open country and crossed a brief plain which has a chain of very tall mesas to the east…

Can you visualize the group of Dominguez-Escalante and their thirteen companions — a retired soldier, a mapmaker, assistants, and their Native American guides and interpreters — passing by this location? What a sight it would have been.

Fur Trappers and Mountain Men

In mid-September of 1826, Jedediah Strong Smith and a company of fifteen fur trappers passed this way en route to California. They were travelling south from an annual gathering of trappers and Native Americans known as the Bear Lake Rendezvous. During their journey, they hunted and trapped in the mountains of Utah and eventually located Ash Creek — following it to the confluence.

The next year, Smith again attended the rendezvous and made the same return journey to California, this time with eighteen men and two women. He passed through the area presently known as Confluence Park in September of 1827, and he later faced armed opposition by Native American groups near the Colorado River. Whether because of this battle or by other circumstance, Smith would never again return to Southern Utah. He would end up passing away in 1931, but his legacy as a prolific explorer and mountain man have led some to consider him a spiritual successor to Lewis and Clark in the colonization of the western United States.

Mormon Settlers at the Confluence in the 1800s

Parley P. Pratt, seeking developable land for Mormon settlement expansion, led an expedition to the confluence in 1849. Mormon pioneer John D. Lee led an exploring party through in the summer of 1853. One of Lee’s party wrote, “We then got some Indian guides, who brought us to the jerks (confluence) of the Virgin, Levier Skin (La Verkin), and Ash Creek where we found a number of Indians raising grain. Their corn was waist high; squashes, beans, potatoes, etc. looked well.”

Nearby Toquerville was settled in 1858. Its residents were the first pioneers to use the confluence property for large cultivation projects. Levi Savage Jr., who moved to Toquerville in the early 1870s, farmed in the confluence area where he grew corn, sugar cane and lucerne (alfalfa). He refers to this farm as the “river field” in his journals and tells of hauling hay, planting carrots, bringing home wood, cutting lucerne, and repairing fences. Two entries speak to both the trials and the delight of his river field:

Dec, 24, 1889: Willie and Riley went to the River Field on horseback; found our ditch badly damaged by the late high waters, but no worse than it had by former floods.

May 6, 1891 :The young folks had a picnic at the mouth of Ash Creek.

Activity in the 1900s

Washington County records reveal that Thomas Stapley (1890), Levi Savage (1901), and Thomas Judd (1901) were the first recorded land owners of the (now) Confluence Park area. Many more followed. A variety of agricultural pursuits would emerge: alfalfa fields, a pecan orchard, a dairy, a turkey farm, cattle grazing, and more.

Washington County records reveal that Thomas Stapley (1890), Levi Savage (1901), and Thomas Judd (1901) were the first recorded land owners of the (now) Confluence Park area. Many more followed. A variety of agricultural pursuits would emerge: alfalfa fields, a pecan orchard, a dairy, a turkey farm, cattle grazing, and more.

Irrigation was a constant struggle. Methods would vary through the years: LaVerkin Creek diversion with an open dirt ditch to a collection pond system to sprinkler-pipe water delivery. Through it all, the only constant would be the unpredictability of the Virgin River, LaVerkin Creek, and Ash Creek: sometimes experiencing historic floods, nearly running dry at other times, but always supporting a welcome oasis full of wildlife and adventure for local residents.

Electrical Power Generated from the Virgin River

The greatest change to the Confluence area came with the construction of a hydroelectric plant on the Virgin River below Pah Tempe Hot Springs in 1929. Victor Hall’s writings, “Selected Topics Related To Hurricane,” make reference to the plant as follows:

The plant that was in operation from 1929 until 1983 utilized water diverted from the LaVerkin irrigation canal. The canal began about three miles upstream. Water first went into a settling pond… a sluice gate facilitated flushing the pond as necessary. Downstream… the canal clung to the Virgin River canyon wall, then went through a quarter-mile tunnel before emerging onto the LaVerkin bench. From this point, a pipe (penstock) forty inches in diameter conducted water to the hydro-electric plant.

The Washington County News reported on April 29, 1929, that operation of the plant had begun, and that, “Fred Brooks, whose family was then living at the plant, would be in charge.” Despite their isolation from the rest of their community, the Brooks homestead was likely a noisy one due to the steady hum of machinery below their second-story apartment. Kay McMullin became the plant’s chief operator in 1958. Unlike the Brooks family, Kay and his family chose not to reside at the plant. He remained on-call for issues and repairs, and would frequently inspect the water supply canal by navigating a precarious path along a steep rocky ledge.

In 1983, Kay returned from vacation to find the plant’s vital machinery in shambles. Although the exact cause for this damage remains unknown, some theorized it may have been caused by a lightning storm or it was sabotaged by a disgruntled former employee. Given the high cost of repairs, rebuilding was deemed impractical. The plant is now on the National Register of Historic Places, and efforts are underway to preserve and possibly restore the plant for its historical value.

Information for this historical summary, including some portions of text, were provided by Leon Brune.